Beaucoup de paillettes, peu de flammes : Rest isn’t always resistance

Care practices have been perverted, stripped of their radical nature. Taken as an end in themselves, they don't just divert struggles—they erase them, replace them. The point here shouldn't be to congratulate ourselves for our immobility, but to confront the place our comfort takes—what we offer or refuse to offer to radical struggle. Rest isn't always resistance.

Wednesday, June 4th marked the opening panel of the 2025 Brûlances festival. Now in its third edition, the radical queer festival wrapped up the following Sunday after a weekend of workshops, discussions, and a big party. Initiated by the Pink Block, and now carried by an autonomous collective, the project serves both as a space for politicization, and a point of entry for many in the milieu.

This text was written a few days after Brûlances, to comment on a few interventions heard during the festival—especially on the matter of whether "rest is resistance". Giving ourselves space to dream about alternative and possible futures; getting back in touch with our bodies, and investing in the forgotten aspects of our lives—rediscovering the extent to which they are empowering; developing care practices that are part of an already existing, prefigurative logic. These are all part of a set of practices that are essential in a revolutionary political project—particularly in an organization that seeks to make it a life project rather than a leisure activity. But also in an organization that seeks to move beyond a feeling of urgency, to act according to its own rules rather than in a reactive way—to become a militant rather than an activist. Yet, in recent years, the popular language of healing, somatic care, and "radical self-care" has rendered the expression 'rest is resistance' meaningless. Endlessly repeated on social media, wellness spaces, and even the IED's institutional framework, the slogan is now far removed from its roots in the radical Black struggles. Once used as a strategy of collective survival and resilience in the face of oppressive systems, it has since been reduced to a depoliticised, individualistic mantra—divorced from its context and used as a weapon turned against the very communities it was meant to serve. To challenge this tendency, we have to put the notion back into the political in which it emerge: the Black Radical Tradition. This tradition rooted in insurgency and resistance sees care not as a retreat, but as part of the infrastructure of the struggle.

The Black Radical Tradition and Collective Survival

The Black Radical Tradition, as articulated by Cedric J. Robinson in Black Marxism (1983), is not a fixed ideology, but a constantly evolving political lineage rooted in the collective resistance of Black people to racial capitalism, imperialism, and colonial domination. It encompasses the contribution of Black communists, anti-colonial thinkers, Black feminists, and revolutionary militants who, across centuries and continents, built movements against systemic exploitation. Crucially, the tradition does not separate questions of care and rest from the broader imperative of collective liberation.

Black feminism, a critical force within this tradition, has long articulated the necessity of rest, not as a privatized act or a detachment, but as a collective survival strategy. Audre Lorde, often cited for her powerful reminder that “caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare” (A Burt of Light, 1988), did not promote rest as political withdrawal. Rather, she insisted that self-care was necessary to continue the work of resistance under violent conditions, including racism, misogyny, and the ongoing assault of the medical-industrial complex. Misusing Lorde’s words to justify avoidance of struggle profoundly misunderstands the context in which she wrote, amid cancer, exhaustion, and unrelenting political engagement.

This is where appropriation begins: when Black feminist insight, forged in the contexts of survival and struggle, is co-opted to support neoliberal self-regulations and individual retreat. It is an appropriation that strips rest of its political urgency and hollows out the transformative potential of Black feminist praxis. Instead of sharing resources for sustaining political action, rest is increasingly marketed as self-optimization, something to be consumed, scheduled, and posted about.

Claudia Jones, Rest and Structural Transformation

To understand rest as within its true political lineage, we must look to figures like Claudia Jones, a Trinidadian-born Marxist and Black feminist organizer, who wrote “An End to the Neglect of the Problems of the Negro Woman!” (1949). Jones was deeply attentive to what she called the “triple oppression” of Black women, exploited as workers, as women and as Black people. She argued that liberation could not be achieved without addressing the full range of material conditions shaping the lives of Black women.

For Jones, rest was never imagined as individual pause, but as part of a larger structural demand: for housing, healthcare, childcare, maternity leave, and dignified wages. These were not one time luxuries, but prerequisites for Black women to live, flourish, and continue organizing. “The most oppressed sections of the Negro people”, she wrote “ are its women.”, and addressing this required organized, revolutionary intervention, not temporary reprieves, but sustained collective action against the systems that produce exhaustion in the first place. In this light, any contemporary illustration of “rest is resistance” that fails to include demands for housing justice, reproductive freedom, labor rights, or the abolition of carceral institutions is fundamentally severed from material solutions that would liberate Black women and Black people as a whole.

Ashanti Alston, Rest As Prefigurative Politics

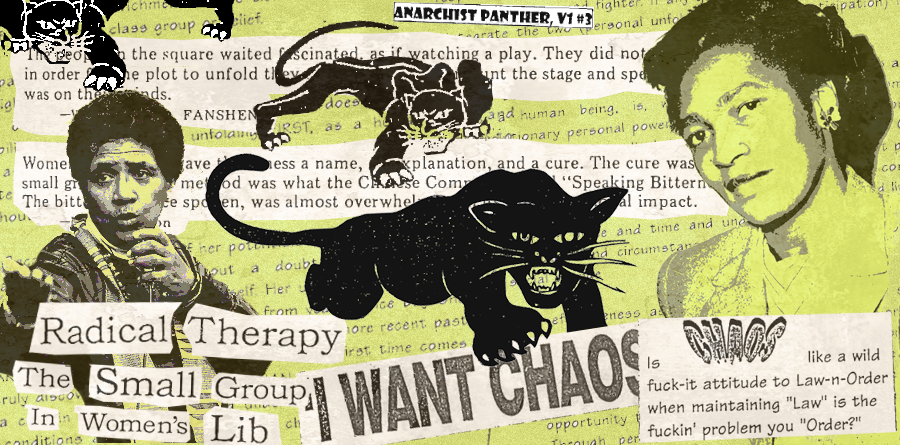

From a Black anarchist perspective, Ashanti Alston expands this conversation by connecting rest to mutual aid and the dismantling of domination in all its forms. A former member of the Black Panther Party and the Black Liberation Army, Alston’s writings and talks reflect a deep commitment to building what he calls “zones of autonomy”. Spaces where new ways of living, relating and organizing can emerge beyond the reach of the state.

Ashanti Alston emphasizes that revolutionary organizing must actively reject and dismantle the same oppressive structure, such as hierarchy and gendered violence, that define the systems we aim to abolish. For him, the purpose of rest is not to escape struggle but to participate in building new social relations that prefigure liberated futures. He continues to articulate that rest is not a withdrawal from political work, but a component of building revolutionary alternatives. His understandings of care is rooted in prefigurative politics, meaning we must build the conditions we wish to see by enacting them now, that we must live and practice the world we seek to build, even before that world has fully arrived. This includes communal childcare, food sovereignty, and neighbourhood defence, not as utopian dreams, but as immediate interventions into the violence of racial capitalism. Alston’s work insists that rest is not restorative unless it is shared. Rest, like liberation, must be collective. Otherwise, it risks reproducing the same unequal distributions of time, energy and care that define the system we claim to oppose. (The Anarchist Panther, Issue 1, 2001)

The False Universality of “Rest”

Let one thing be clear: Not all Black people get to claim rest as a spontaneous act they can make whenever they like. For the working poor, the undocumented, the incarcerated, and the unhoused, rest is not a spiritual awakening, it is a structural impossibility. These communities exist within systems designed to extract their time, energy, and lives. They are policed by exploitative labor regimes that demands constant productivity, surveilled by the carceral state, and crushed under the weight of racial capitalism, the very system that uses racial hierarchies to justify and sustain economic exploitation. To speak of rest as a liberatory act without confronting the oppressive structures that make it unattainable for these communities is not just hollow, it is violent. It erases the reality that for many, rest is not a personal choice that can be simply made on a whim, but a luxury that cannot be afforded easily.

What part of the radical Black tradition alludes to telling, say in this case, a Black woman who might be working two low wage jobs, juggling the high costs of childcare, and constantly battling housing insecurity, that she simply needs to choose rest? There is no form of resistance in prescribing rest to someone who risks eviction, hunger, or criminalization the moment she stops moving. It is deeply disingenuous and profoundly cruel to romanticize stillness while completely ignoring the material conditions that prevent it in the first place.

Rest can only be resistance when it is earned through struggle, secured by solidarity, and shared among the most marginalized. Until we confront the structures that perpetuate inequality, the rhetoric of rest will remain hollow. It will remain the luxury for the select few, while the rest of us continue to labour under systems that demands endless toil. Only when we dismantle the stems that make rest a commodity for the few can we truly claim rest as resistance. Until then. It remains nothing more than a dream, far out of reach for those who need it most.

Here and now: care as a revolutionary necessity

That practices of care help support our struggles and the long-term commitment of people involved is, of course, something we wish for. But under neoliberalism, only the most self-indulgent, least radical versions—those that are deployed as an end in themselves, rather than in support of struggles—get to be legitimized. Revolution is a real political horizon. We won't get there only through performative rhetorics. Yet, although we are critical of practices centred on our inner selves, on our intimacies—those that aren't articulated to overthrow power—we still value those practices that are based on prefiguration as a strategical approach.

To conclude, we propose a short reflexion based on our analysis of current contexts. These reflexions emerge from the urgent need to do better, to move beyond the perceived opposition between care and struggle, and to move away from both moral and radical purity.

Many initiatives that focus on preconfiguration—even when they are conceived as part of the revolutionary ideal—are dependent on vast amount of resources, with some successful, yes, but limited results. These initiatives usually benefit only a handful of people, and always emerge as a reaction to something. As a form of palliative care. They thus reproduce the conditions from which they emerge. How can we develop decolonial care practices if not by dismantling capitalism?

<br

Prefiguration, as a form of discourse, makes it helpful to prepare ourselves for what's to come, but it should never serve as an excuse to withdraw from our struggles. Dreaming about, and imagining alternative worlds is a revolutionary necessity. But let's not only dream for ourselves. Let's offer the world, in concrete ways, the fruits of those dreams. We can even go further. Let's get organized. Let's not only write, but set in motion the steps that will lead us to these worlds.

Obviously, our minds are colonized by having internalized the dominant systems of oppressions that structure our lives. However, killing the cop in your head won't slow down the fascists' rise to power. Decolonizing your brain won't undermine imperialism. Gently holding space won't dismantle the state. Treating care and rest practices as inherently radical—even when they are not (directly) tied to a revolutionary project—only serve to depoliticize them. Micro-politics disconnected from macro-politic is not revolutionary. Focusing our energy exclusively on these practices, without putting ourselves on the line as political subjects, or without questioning our comfort, only serve to immobilized us.

This inertia is desired and imposed by dominant forces:

- either by crushing us, making us miserable subjects trapped in survival mechanisms;

- by assaulting us with atrocities, rendering ourselves powerless, or de-sensitised, numb;

- or by convincing us to engage in 'resistance' practices that are genuinely harmless to the established order, and that keep us pacified.

We are just as critical of certain care practices as we are of certain combative ones.

The care practices that we denounce are like a heart removed from the body it could have sustained. A paralyzed heart, as described above. The combative practices we critique are those that, though exhilarating, resemble an amputated arm. An arm that acts more by reflex than by reflection. We keep on losing, and we are not even able to wipe our own asses—that is, taking care of our comrades, being accountable, taking responsability. The idea would be to put care at the service of struggle. To fight hard, but wisely and strategically. To build a solid body whose vital systems support each other in order to move forward. In practical terms, this means setting up infrastructures, shifting cultural norms, and empowering ourselves to meet our immediate needs—particularly in terms of mutual aid—while also seizing the means to sustain and reproduce our struggles over time.

But if we are to organize on our own terms, there is an urgent need to create a space for a serious and structuring dialectic—one that would allow us to learn from our mistakes, identify our pitfalls, analyze our victories, and shape the future of our struggles. A dialectic that offers us a direction, and around which we can mobilize and rally as accomplices. It would be a space for conflicting ideas, tied to care initiatives. As space where strong propositions collide, and where both criticism and alternatives are welcomed. But this doesn't mean that we should embrace everything without any discernment. Some propositions, discources, and practices—such as those that de-historicize and de-politicize care—are harmful to our combative efforts, and we need to distance ourselves from them. We need to find our bearings again, and to reanchor these practices that have drifted away, before we lose ourselves in a neoliberal tide. It's not a matter of differing interests or opinions. What immobilizes us—it's worth repeating—is the discourse that gains traction either because it flatters newcomers, aligns with dominant cultural norms, or offers more comfortable kind of indulgence.

Rest is resistance: if it means helping each other to manage our suffering, to get our of survival mode, and to free up our time and energy—to mobilize aroung the fight.

Rest is resistance: if it means getting out of a constant state of activation in the face of horrors, so that we can face them better and see further ahead.

Rest is resistance: if it means giving ourselves the means to make a lasting and tenacious commitment to putting an end to all systems of oppression.

Cited Texts

Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Traditionby Cedric J. Robinson

A Burst of Light by Audre Lorde

An End to the Neglect of the Problems of the Negro Woman by Claudia Jones

The Anarchist Panther, Issue 1, 2001 by Ashanti Alston

Feel free to disregard this: i think the text is hard to read due to the academic language. I am a big fan of what bell hooks says on why she choose the language she did and to walk away from academic language. I find it more inclusive.